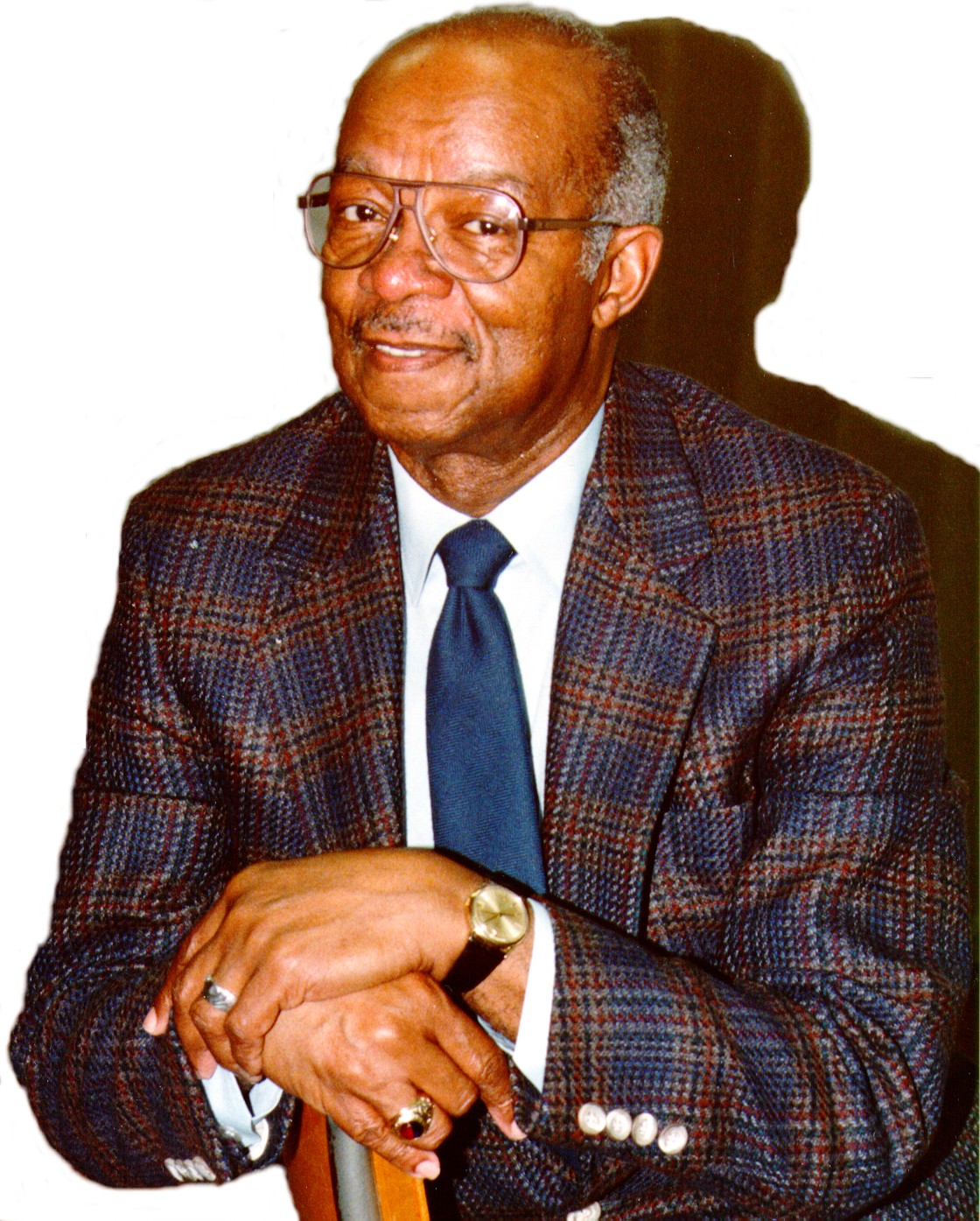

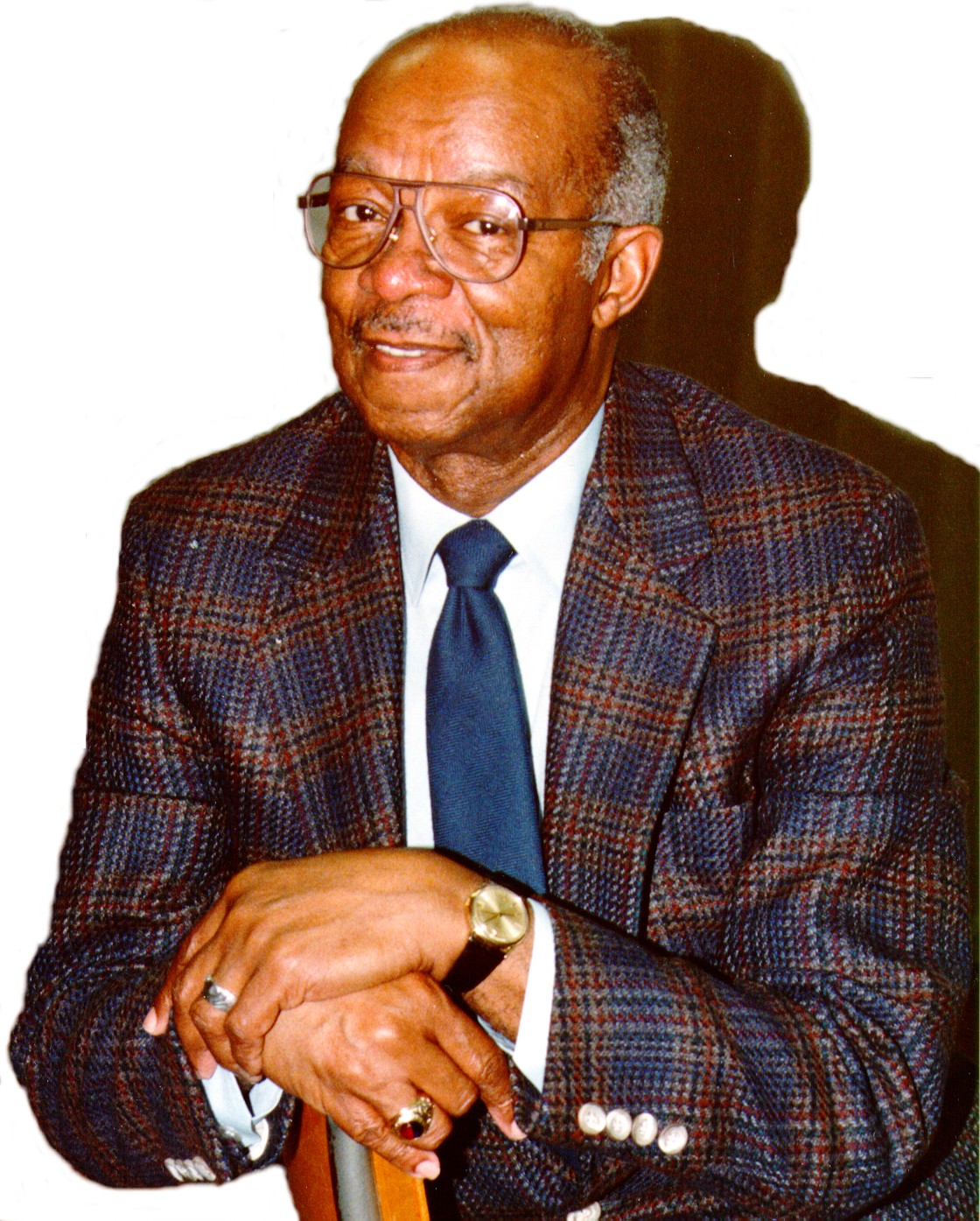

Professor James T Harris was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in June 1922. With a graduate degree in Social Work from the University of Pennsylvania and a Bachelor of Arts Degree in Music from the Philadelphia Musical Academy and Temple University, he was Associate Professor of Social Work at Renison College, University of Waterloo in Waterloo, Ontario. He retired in June of 1988 but continued to teach the course “A Christian Perspective of Social Work Practice”, which he developed. The following is an excerpt (by kind permission of the author) from his Monograph entitled “Yea, I Have a Goodly Heritage”

I Am a Black Canadian

Vol 7 1998

I was not born in Canada. I emigrated from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania twenty eight years ago intending to make a life and establish my home in Canada, preferably Ontario. I have fulfilled that intent and have been basically happy and pleased with what I found in Canada as a country and in Canadians as a people to be. I am very proud to say, “I am Canadian!” However, there are times when I am made to feel like a total stranger in this land, a misfit, a second-class citizen. I do not enjoy such feelings, and I am sure that many other blacks and people of visible minorities agree with Headley Tulloch when he says this:

All Canadians were immigrants at one time or another. But when it comes to blacks, the native peoples, or Asian minorities there is a difference. A high contrast in colour or other marked physical differences create a certain reaction from the majority members of most societies. An immigrant of, say, Italian or Polish background can blend into the general population over a period of years, but a black person cannot change his skin colour. This makes his experience different from other newcomers’

Most black immigrants experience racial discrimination here at some time or other. Those who have been unfortunate enough to repeatedly have racist attitudes beamed at them become very sensitive about their blackness.

I have experienced racial discrimination in Canada, not always blatantly, but certainly in many subtle and not so subtle ways that cause me to be very conscious of, yes, and sensitive about my blackness. So, life for me as a black man in Canada has been no different than life for me as a black man in the southern part of North America. I still have to deal with those Canadians who see me as a black man first and foremost and, possibly, as Jim Harris, the individual and human being, second.

I have held very good positions here in Canada, and I have a comfortable home and lifestyle; I have many friends and colleagues who accept me for who I am, not what I am.

However, there is a certain part of life that seems to elude me.

It is known as inclusion! It is that feeling of full acceptance for being the human being that I am; it is knowing that I am viewed as a person, first and foremost, and that just by happenstance, my skin is black (really brown, but that is a topic for later).

Socially, the black population of Canada is growing; politically it is being looked at in terms of the racial problem that exists for all or most minority group immigrants. Both of these are good, but they are relative to the political and economical position and the empowerment of minority groups. We should not lose sight of what the individual minority person is feeling about his or her acceptance, power, and basic social functioning and rights in the community at large.

Headley Tulloch states that black Canadians can help us, both black and white, to understand the background of the myths about black people. These myths form, or confirm, negative notions about black people. He refers to the jokes and myths that have been perpetuated by generations of white people.

Like “Newfie” jokes, which give an image of a people who are stupid and incapable of learning, “nigger” jokes portray a false picture.

That many things which white people say and think about black people are untrue does not mean that they do not hurt.

Some of these comments make me and other black people feel angry and unsure of ourselves … or make us want to do things that we would not ordinarily do. The word “nigger”, for instance, is most repulsive to blacks. It signifies the massive historic injustice heaped on black people for economic gain as well as the white attitude of superiority. Today, most blacks prefer to be known as “black”, the opposite of “white”, or prefer “Afro-Canadian”, a blend of our heritage (African, in most cases) and our adopted country, Canada.

Strangely enough, although the colour of our skin is viewed negatively by some white people, many of them spend thousands of dollars trying to obtain a more healthy-looking brown complexion. They call it “suntanning”. It’s ironic when you think of how they often disdain people of other cultures whose skin is naturally dark. Actually, no one is really “white”

People of the white race are actually pinkish, beige or light brown. When people expose their bodies to the sun, they develop a darker skin because the body produces more melanin to absorb the ultraviolet rays. If you are a black person, it means that you automatically have some natural protection against ultraviolet rays.

The same is true for black people’s eyes. They are protected from the sun’s rays by the melanin found on the inside of the white and on both sides of the iris of the brown eye. It serves the same protection as a pair of dark sunglasses do. People with blue eyes do not have this same protection from dark sunlight. The thick, curly or woolly hair, so characteristic of black people, is another design of nature. This type of hair forms air pockets and serves as a natural insulation, protecting the brain and scalp form dangerous rays. The flat nose is yet another natural environmental adaptation to escape the full force of the sun’s rays. White people with prominent noses find their noses are susceptible to sunburn. White lifeguards usually tape their noses as a protective measure.

It is necessary to explain these facts because, even today, we find people confused about the question of differences in colour.

This has led to unnecessary difficulties in understanding that we all belong to the same human race, despite differences in nationality, customs, beliefs and physical characteristics.

Racism is a social disease, and it will continue for more years or generations than I like to think. With that in mind, coping with racism for me is a way of life and will be for the rest of my time on this planet. However, when all is said and done, my coping mechanism comes down to my faith in God who has created me and given me faith in myself and faith in significant others in my life. And I also have a heritage that is based on a foundation of faith. That faith was, and still is, being demonstrated by the blacks in Canada who are dealing with racism in a way that brings to the fore, to the attention of Canadians of all races, the commandment to “love one another”

It takes a lot of courage, strength and faith to live in an atmosphere where one is always unsure of being accepted. Our faith has always helped us live in a social climate fraught with myths about who we are as a race and, in some minds, about who we are as human beings. My knowledge of the Black history in Canada is as much a part of my heritage as the Black history of my ancestors in the United States. The strong faith of the black slaves who arrived in Canada through the Underground Railroad, of those blacks who were born here, and of those who have come from other countries, has demonstrated their ability to deal with their blackness in North American society. I am proud to be a part of this present era of Canadian Black history, when so many Canadian blacks are contributing to family life, to politics, to sports, to arts and culture, education, science, religion and social welfare.

Martin Luther King, Jr., in one of his many elegant and treasured speeches, had this to say about Canada:

“Canada is not merely a neighbour to blacks. Deep in our history of struggle for freedom, Canada was the north star. The black slave, denied education, dehumanized, imprisoned on cruel plantations, knew that far to the north a land existed where a fugitive slave, if he survived the horrors of the journey, could find freedom”

The sequel appearing in Cross Cultures (by kind permission of the author) from his monograph entitled “Yea, I Have a Goodly Heritage” will resume after this exclusive article, which was inspired by Black History Month.

Professor Harris passed away last September 1999, he was a good friend to many people, of whom Cross Cultures editor/publisher is proud to be one; he was a very kind and gentle person, who cared about his fellow human beings, always listening patiently and advising with great wisdom. He lives on in our hearts

A Legacy of My Black Heritage

Vol 9 2000

February of each year has been designated as Black History Month.

It is a special time for us, not only to display our black culture and history in various places but it is a time to celebrate within ourselves.

I have found it to be a time of inner reflection for me as a Black man in North American society. A time to individually and collectively assess our sense of pride and to identify who we are. We are a great people – we have a goodly heritage. We are God’s creation .. God’s children!

More and more I find myself getting involved in activities, giving presentations or attending scheduled events in the area or other parts of the province. I felt compelled to take a few moments and truly think about aspects of my Black heritage and culture and its impact on me. I again found myself focusing on the many legacies left to me and us by our ancestors who were slaves. I became captive of my thoughts of the incredible life they lived and endured all of those many years. At times I see their survival as a miracle. How on earth did they do it? What was at the base of their endurance, courage, strength or determination? No matter how much I thought I gave to these questions academically, historically, psychologically, or sociologically, the answer was the same. It was, without a doubt their indomitable hope, deep faith and persistence!

Our ancestors had great hope, pride strong faith and a sense of who they were in their relationship with their God. Even in the midst of the terrible trials and tribulations of their lives as slaves, they are known to have contained a sense of inner peace that served as a source of tremendous inner strength. This faith and hope they displayed is a legacy that I personally find is the source of my ability to cope with the injustice, prejudice and inequality our race faces in today’s society. As Black people, we are on a journey. A journey that is fraught with unexpected and mammoth roadblocks. A journey in which we are still struggling to achieve a better life and place in our society. I think struggle is inherent in our heritage, and I often wonder why .. why us .. why me? However, I like to think -as silly as it may sound- that there is a purpose in this particular aspect of our lives as Black people.

Don’t ask me what that purpose is.

I often have that conversation with my God, but have not received a reply yet; however, in the meantime, I don’t give up on life .. or the journey. As I look back at my life it has been good, in spite of the thorn of racism being ever present along with all of the other problems that are entailed in the struggle of our Black race. I have succeeded in many of my goals and endeavours in life and overcame the other obstacles that constantly rear their ugly heads on my journey. In fact, as I grow older – and hopefully wiser – I have come to realize that my faith in God has given me endurance and strength beyond my own expectations in certain situations that I have had to encounter as a Black man in a white society. I deeply believe in the words of Psalm 46 as written in the Bible of my Protestant faith ..

“God is my refuge and strength,

a very present help in trouble”

What a discovery ..what a joy to know I/ we do not have to walk this journey alone!

Over the past several years I have pulled together my thoughts about racism and my faith and the impact they have on me as I live my life. One of the purposes of the book “Yea, I Have a Goodly Heritage: My Faith, My Life and Racism”, I wrote two years ago – and recently e-issued – was to come to terms, in a more tangible manner, with this facet of my life. I put my feelings and thoughts on paper where I could see them in a larger context than just separate incidents occurring along the journey. It was also my hope that its contents would send the message to my Black brothers and sisters that they are not alone on this journey.. all of us travel this Jericho road, so to speak, but there is a uniqueness about each of us, as individuals, and the way we experience, express and handle our thoughts and feelings, but there are commonalities also. While sharing my experiences in this book I attempted to present and bring to the fore, the power of a facet of my Black heritage, which is faith, hope and trust. At the same time I hope it will be read by my white brothers and sisters in our communities in order that it may further educate, inform and expose them to yet another aspect of our goodly heritage and Black culture.

Bishop Desmond Tutu, in his book, Hope and Suffering, states,

“when the oppressed are freed

from being oppressed –

the oppressors are freed

from being oppressors”

It is my sincere hope that, with the new millenium, African Canadians will stay focused on the faith of our ancestors and its relatedness to our past, our present and future as citizens of North America.

Our faith, hope and inspiration is well grounded in the past struggles and pain, achievements and contributions of our unique people ..it can be seen and felt as we look inward and discover “the stuff we are made of”, such as the exceptional courage of those persons who participated in the saga of the underground railroad; the unrelenting determination and persistence of our slave ancestors and settlers who trusted and had faith in the North Star to direct them as they made those perilous escapes from the cruel life on the plantations of the south and forged ahead, to make it to the “promised land” they dreamed existed in Canada .. the inspiration of our modern Black leader, Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King, whose faith in God and trust in the Black people, and other significant people, Black and White, who joined him in his cause and fight for freedom, equality and justice ; the steadfastness and limitless energy of all the individuals who shared his dream and their own that, in time, would break new ground in the area of civil and human rights, justice, respect and recognition… the hopes and dreams of our Black youth as they endeavour to succeed in the footsteps of committed, concerned and loving parents, teachers and outstanding role models … the faith and guidance we see demonstrated daily by our Black men and women in the ministry who promote peace and harmony dignity and peace among the races and inherently declare the love of God for all of us regardless of colour, race or gender .. we are all God’s children … the self-determination and the sincere and selfless efforts of our Black artists (from the various genre) as they continue to attempt, through cooperation and coordination, to bring the worlds of Black and white closer in the areas of art appreciation, knowledge and respect.

The history of Black people has been woven in the fabric and etched in the cornerstone of the history of Canada and the U.S. in many ways and by many Black people. This fact cannot be ignored, dismissed or forgotten. We must not allow that to happen.

Ours is the history of a proud people who have a continuing and growing faith in God. Ours is the history of a proud people whose struggle, pain, determination, gratitude and yes, joy, has brought them out of the depths and pits of degradation and into the light of the world – God’s world. Ours is a history of faith illustrated and told through our immortal music.

Ours is a historic journey that is rich regardless of the rough up-hill climb toward acceptance and recognition, but hopefully, it will be made smoother by each ensuing generation.

As I ponder Black History as it has occurred from the era of slavery to the present, I find affirmation of my belief in the fact that our Black ancestors, in spite of the horrible life inflicted on them as non-persons, left us a legacy of Faith and Hope.

We have been given a legacy of hope that allows us to be faithful and effective, that enhances our ability to cope with the social conditions of our lot in society today.

Racism : The Jericho Road

Vol 10 2005

My attempt to live my life as a Christian compels me to be concerned about the ill-treatment of and prejudice against all people who suffer disfranchisement because of nationality, language or colour of their skin. This compelling concern for all people regardless of race, religion, colour, creed or gender is substantiated in Paul’s letter to the Galatians: ” … There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus”. And it is further substantiated in the Scripture according to St. Luke: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind; and your neighbour as yourself”

The story of the “Good Samaritan” on the Jericho Road is the theme of this chapter. My faith tells me that I, as a member of a minority group, not only am responsible for looking for, expecting and accepting compassion from others, but also have a duty to reach out in love to my neighbour. Having been the victim many times as I travelled the “Jericho Road” during my lifetime, I can easily identify with both the victim and the Samaritan of the story. I thank God for the many Samaritans who have played a part in my life when I was victimized.

Conversely, I am deeply concerned about the seemingly increasing number of people who choose to distance themselves from situations where racial prejudice or racial maltreatment or injustice is evident. The story that Jesus tells is a story of acceptance, caring, spontaneity- a story of compassion first, and I am sure that nationality never entered the mind of the Samaritan. There is a potential Jericho Road in every city, town and community of Canada and the United States. Whether they have different names, like Yonge Street, Fifth Avenue, King Street or Main Street, they all have the potential of being a “road” where non-acceptance of persons from minority groups or certain cultures is practiced, where non-involvement and passing by on the other side is natural behaviour, where racial slurs and overt taunts are daily occurrence.

They are “roads” that are fraught with disrespect towards anyone whose skin is dark, whose apparel is culturally different from that in the community, whose language has an accent that is different from the language usually spoken in the community. The “traveller beware” signs on these roads are often obvious, on some of the roads, the signs are subtle but the victimization is just as rampant.

Victims of the Jericho Road

I, and many persons of minority races frequently travel on the Jericho Road as we journey through life. On this journey, we seek only the right to a life of dignity and respect; the right to develop our potential, the right to be contributing citizens of our community, the right to love and be loved, the right and desire to be accepted as the individuals we are. However, our reality is that of constantly encountering robbers, Levites and priests who attack us physically, emotionally and psychologically – dehumanizing us and stripping us of our dignity, incentive and pride.

There are modern-day robbers in our local community who, when they meet someone whose skin colour, accent or dress is different, cause pain and injury by blatant acts of prejudice. There are Levites in our community who pass by us with subtle acts of discrimination, avoidance, non-acceptance and bigotted attitudes. And there are also certain ‘priests’ in our community, some of whom call themselves Christians who say they care about us and will help us in any way they can as long as it does not require them to touch us, live next door to us or enter into a relationship with us. We can find the victims of the Jericho Road in our communities if we take the time to look or read our newspapers.

One such victim is Chinh Hoang, a graduate of a Saigon medical school and a political refugee, who lived in one of our local communities in Ontario. Chinh immigrated to Canada in 1983, believing he could practice here, but he soon faced many obstacles even after passing the Canadian medical examination and English tests. Because Chinh Hoang is constantly being told that there are no openings as hospital interns for foreign-trained people, he supports his family by cleaning, delivering newspapers and washing dishes. Chinh says, “The biggest barrier is racism. It’s the enemy of this country.

I’m afraid my children will face the same trouble because of the colour of their skin”

Another victim is Rajah, a University of Waterloo civil engineering student, born in India. Rajah learned from a sales clerk in a prominent local stereo shop that Waterloo Region is not immune to racism. One day, while searching for a stereo component, he was abruptly abandoned by the sales clerk who left to wait on a white couple who had entered the store. When the couple left, the clerk returned to Rajah. Just as he had not excused himself when he left, neither did he apologize upon his return. Rajah was told that the stereo component was not in stock but could be ordered, so the clerk took his name, address and telephone number, saying we would call when the part came in. Leaving the store, Rajah heard the clerk tell another employee to throw the order in the wastebasket. He has not heard from the store since.

An unfortunate survivor of nineteenth-century America is the saying “The only good Indian is a dead one.” Sad to say, there are still people today who hold this opinion. It is confirmed by a recent headline in the Canadian newspaper:

“A Native’s Life is Pretty Cheap In This Country”

The story told how a Saskatchewan white supremacist had killed a Cree by shooting him in the back with a high-powered assault rifle.

When the offender was arrested, he told the officer, “If I am convicted of killing an Indian, they should give me a medal”. The offender may not have got the medal, but he received the legal equivalent: a four-year sentence for manslaughter. The message sent by the Saskatchewan justice system is this: If you kill an Indian, you’ll be a free man in four years.

Compare that to the case of Donald Marshall – a Nova Scotia MicMac who spent 11 years in jail for a murder he didn’t commit – and you can well understand native anger at the justice system. The convicted supremacist’s action was an extreme manifestation of the hatred felt toward aboriginal people in this country – – but it is not the only example. Most racism is much more subtle. It isn’t likely to be making headlines or driving inquiries across the country.

continuing . . .

Vol 15 2006

Another native victim along the Jericho Road in Canada was the 14-year-old MicMac hockey player in Truro, Nova Scotia, who was the object of racial slurs in a highly publicized playoff game. Mike Marson, only the second black hockey player (1974-1980) in the history of the NHL, had this to say about the incident “I experienced such incidents many times. In fact, hate mail, crank calls, and death threats were not uncommon. It is beyond me how such bigotry can still exist at an event where colour, race and creed are not prerequisites.

Wake up, people! In seven years we will embark on the 21st century. Isn’t it about time that we, as Canadians old and new, begin assessing each other on authentic capabilities, and not on colour, creed or whatever?

Two years ago on a Jericho Road in Tampa, Florida, a 17-year-old, a 26-year-old and a 33-year-old were charged with attempted murder, armed kidnapping and armed robbery in an attack on a 31-year-old black male tourist. He was doused with gasoline and set on fire. A racist note at the scene of the blaze was signed “KKK”. The victim survived but required skin grafted surgery to repair second and third degree burns over 40 percent of his body. He said that his attackers taunted him saying: “You’re a nigger, boy, and you’re going to die. One more to go.” The victim’s mother said: “I want his picture taken so people can see his pain.

I want everyone to see what people are capable of doing over skin colour. I want people to see how ugly racism is”

Sometimes the Jericho Road victim is just a child. Several years ago, just before Christmas, a little boy, in an unprovoked attack, was beaten by three boys with fists and hockey sticks while a fourth stood and cheered. In a letter to the Kitchener-Waterloo Record, the boy’s mother wrote:

“I too have a Christmas message in this Yuletide season. I do not speak of charity or sympathy or goodwill, for these are empty terms in a community which would condemn a little boy for the colour of his skin; I ask you to think well of what you say and what you do in the privacy of your own home that would lead your children to spit on my black son’s toys, to beat him with their hockey sticks, and, worse even than that, to label him “nigger”

This last account immediately reminds me of a song from the very successful musical South Pacific. In the story, a young white Naval officer from Pennsylvania falls in love with a native girl on the South Pacific Island where he is stationed during World War II. Although deeply in love, he breaks off the relationship when he realizes that he cannot marry her and bring her to live in, and be accepted by, his white society. In frustration at having to make

this decision, he sings one of the most poignant songs in the show:

” You’ve got to be Carefully Taught”

You’ve got to be taught to hate and fear,

You’ve got to be taught from year to year,

It has to be drummed in your dear little ear,

You’ve got to be carefully taught.

You’ve got to be taught to be afraid

Of people whose eyes are oddly made,

and people whose skin is a different shade,

You’ve got to be taught before it’s too late,

Before you are six, or seven or eight,

To hate all the people your relatives hate,

You’ve got to be carefully taught.

Oscar Hammerstien II

Such is the nature of racism – a destructive, self-perpetuating sickness, passed on from one to another … infiltrating our world, our homes, our schools and, unfortunately, our churches. Racism is a sickness which can exist without anyone’s realizing it.

Racism is a disease that cannot be measured by statistics. Rather, it often lives and grows just below the surface, manifesting itself in behaviours not easily proven. Rajah, whose story I have shared, says this: “It’s just a feeling you get. But it’s out there. It’s not always visible but you can tell from the way people look at you, talk to you and treat you”

In Canada, racist behaviour ranges from the lowest Newfie joke to the sophisticated political arguments such as those that often take place within the House of Commons when discussions regarding Native Rights and land claims are the subject. Canada’s cities are not lily-white and it’s increasingly tough for us to pretend that we’re the world’s most tolerant and unprejudiced people. Those of us who read our local newspapers and watch daily television news know that racism is common in Canada. It is evident in the story about Native leader, Ovide Mercredi’s appearance before Quebec’s National Assembly and his comment, “To deny our rights to self-determination in the pursuit of your aspirations would be a blatant form of racial discrimination.” It is evident in newspaper editorials expounding our need to label minority persons as Chinese-Canadian or Japanese-Canadian, even if the individual had been born and raised in Canada. It is evident in John Keily’s newspaper article, “Sick Remarks About Waterloo Slayings Are Disturbing,” appalled that some believe the victims at the Ontario Glove Company were at fault, that “the real problem was immigrants taking jobs away from good Canadians”. It was evident a few years ago, when two members of the Immigrant and Refugee Board, in an exchange of notes, micked a young claimant who was describing the torture he suffered in Iran.

Robert Wong, Ontario’s Minister of Citizenship in 1990, said, “The proportion of Ontario residents who are members of visible minority groups is expected to nearly double over the next 25 years…rising from 8 percent of the population to 15 percent. The diversity is bound to increase, since a growing population of immigrants to Canada comes from areas such as Southeast Asia, South America and Africa, rather than the more traditional European sources. This makes it essential, ” he said, “to find better ways of dealing with cultural and racial diversity”